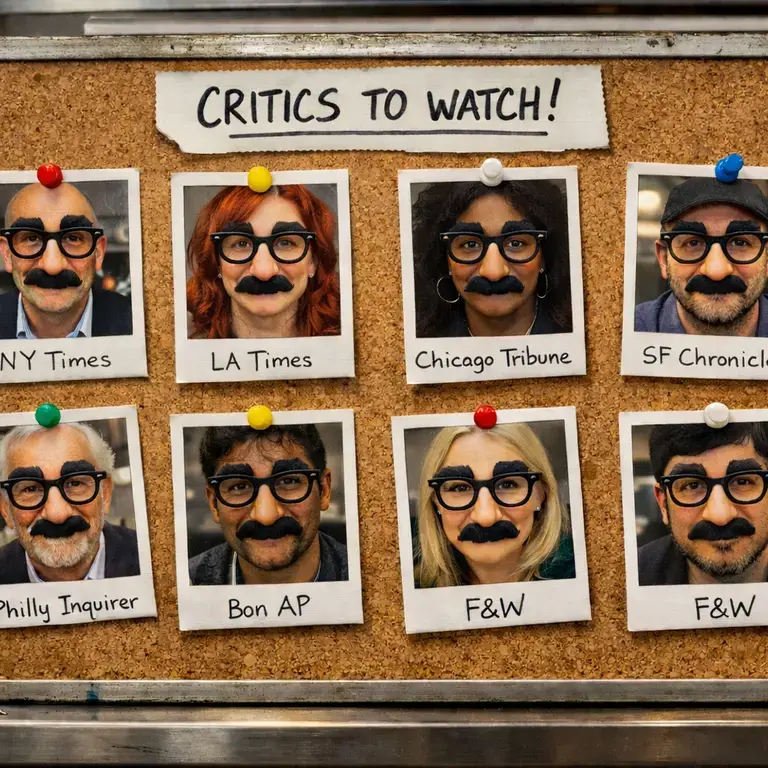

Put away the wigs and ditch the disguises. Food critics are out in the open now. Once little more than bylines atop newspaper columns, they now come with faces attached. In early December, Bill Addison, the restaurant critic of the Los Angeles Times, became the latest to drop his anonymity in a video published by the paper. “Here’s my face,” he says, seated before a wall of newspaper clippings and visibly uneasy. “Video, more than ever, is how journalists of all kinds reach you.”

Addison was hardly alone. Earlier this year, when Pete Wells stepped down as restaurant critic of The New York Times, the paper appointed Tejal Rao and Ligaya Mishan in an unprecedented move, splitting the role between two critics for the first time. The transition was accompanied by a promotional campaign that brought both onto major television programs, effectively ending any remaining notion of anonymity. “I think it is unrealistic in this day and age to maintain anonymity short of being a CIA agent,” Mishan said. Rao was even more direct: “I love the idea of not playing the game of anonymity.”

The shift has also reshaped food criticism at The Washington Post. Upon announcing his departure, longtime critic Tom Sietsema chose to reveal his identity after a quarter-century spent reviewing restaurants in disguise and declining photographs. His successor, Elazar Sontag, followed suit, recording a video and publishing an introductory piece in which he wrote that “his arrival marks a break from one particularly steadfast tradition (…) of remaining anonymous throughout [his] career.” He added that “any chef or reader who cares to know what I look like need only scroll up to my byline.” As he put it himself, “Namely, for our purposes, the internet took an ax to mystery.”

When Anonymity Stops Making Sense

Some critics argue that abandoning anonymity allows for more open exchanges with restaurant staff and diners; others say visibility helps rebuild trust with readers. But the most revealing explanation may be the simplest: “forgoing disguises means that they can talk to the readership directly,” as Sontag points out. Together, these moves signal a turning point for food criticism in the United States, raising a larger question about whether the profession is being renewed or quietly surrendering the conditions that once defined it.

The end of anonymity and the turn to constant visibility reflect a recalibration by legacy publications adapting to a media ecosystem shaped by influencers and content creators, where restaurant visits unfold in real time, faces front and center, plates framed for the camera. Less an ethical shift than an attempt to repair a fractured relationship, this move seeks to reconnect newspapers and drifting readers, critics and overwhelmed audiences, and journalism with a public looking for someone they can trust when deciding where to eat.

“From the readers’ point of view, expertise is not that important anymore. What matters is personal experience,” says Fabio Parasecoli, professor of food studies at New York University. Parasecoli, who previously worked as a food critic for the Italian publication Gambero Rosso in the United States, sees this shift as part of a broader displacement of authority in contemporary society, one amplified by social media and the growing influence of digital creators, generating a broader mistrust of expertise in many fields, food included.

As he puts it, “People don’t follow influencers because of expertise, but because they resonate with their own experience.” The notion that critics should be not only voices but also recognizable faces reflects a growing demand for immediate trust, one shaped by faster, more transactional patterns of connection. “There has been a democratization of food criticism, and that’s a positive thing, even if sometimes standards might go down. If critics want to remain relevant, they have to play the game as it is played today,” he adds.

For Krishnendu Ray, a colleague of Fabio Parasecoli at New York University, social media and digital platforms dramatically expanded access to writing and circulation, reshaping a field that for decades was narrow, homogeneous, and tightly guarded. More women, younger voices, and writers from non-Euro-American backgrounds entered the conversation, bringing visibility to cuisines that had long been marginalized and expanding the very language of food criticism.

According to Ray, a food studies scholar at NYU and the author of many books, including The Migrant’s Table, this shift is not merely structural but symbolic. “The role of the restaurant critic has been moving from a gourmand since the 18th century to a conscientious consumer in the 21st century, one who must attend to questions of sustainability and inequality,” he says. The dominant figure of the male gourmand, shaped by Enlightenment-era France and canonized by figures like Brillat-Savarin, has lost its authority. “That male gourmand as a critic is finally dead,” Ray adds. “And there is much to celebrate there.”

Yet the democratization of food criticism has come at a steep cost. The explosion of voices has not translated into better labor conditions; on the contrary, it has coincided with the erosion of pay, standards, and professional stability. “There are millions of writers and posters now, while only a few are paid to write, and even fewer are paid well to write well,” Ray notes.

At the same time, criticism is increasingly shaped by an image-driven media ecosystem. “We also have more pictures and more videos, to the point that New York Times restaurant critics now have to appear on camera, and less writing,” he says. The result is greater immediacy but diminished discernment, reflection, and careful prose. As the range of cuisines deemed worthy of criticism has widened, the critic’s ability to make nuanced judgments has weakened. In its place, shortcuts proliferate: proxies, stereotypes, and simplified markers of authenticity. “Democratization, paradoxically, has fueled new forms of influence and reduction,” he concludes.

When Critics Are Asked to Perform

The food and cultural writer Alicia Kennedy, author of the influential newsletter From the Desk of Alicia Kennedy, points to the deeper logic of platforms themselves. “They reward sameness and broad appeal, not the most innovative, interesting, or informative work,” she argues. To function on social media, criticism must be diluted and adapted to formats designed to drive views, a process that runs counter to the ambition of saying something new, or saying it in a new way.

“Institutional media companies are effectively forcing critics to become influencers, which I find absurd,” Kennedy says. “It never lands the same way as the content people actually go to social media for. Instead of letting critics do their job, which is to write, they are wasting time and energy speaking to the camera.” She is skeptical of the payoff. “I very much doubt it brings in readers.” For Kennedy, what’s needed is a fundamental shift in priorities, one that shows a broad readership that food deserves more intelligent conversation, and that its significance doesn’t have to end at the table.

For Emily J. H. Contois, an associate professor of media studies at the University of Tulsa, the current crisis in food criticism is inseparable from the long divestment in traditional journalism and the ethical frameworks that once shaped the profession. “Journalistic ethics don’t necessarily guide those creating food-based entertainment, content, or personality-driven media,” she notes. As fewer outlets maintain dedicated critics on staff, expertise itself becomes more fragile. “The risk is for criticism to become public relations, as under-resourced publications just reprint what PR firms submit,” she adds.

Contois does not reject the new media landscape outright. She imagines trained journalists and influencers working side by side, “affording complementary skillsets rather than competing for authority.” The problem arises when entertainment displaces criticism instead of expanding its reach. In a moment of growing resistance to expertise, that shift has existential consequences. “Food critics, at least those trained in a journalist tradition, think deeply about bias, balance, and fairness,” she says. “Visibility can be a challenge, but they have a set of tools to navigate it ethically.” That, she adds, is different from being “an influencer who is always simultaneously building a personal brand and creating content, even if it aims to be critical and informed.”

Social platforms, Contois acknowledges, can draw new audiences to food writing. But their emphasis on extremes risks pushing judgment toward the sensationally good or catastrophically bad. “This is why responsible, informed critique and storytelling are important,” she says. “That kind of work can be packaged into quick, short, and engaging content, but it takes a broader mission or set of values and ethics.” Still, she remains cautiously optimistic. “Even as digital tools have evolved, from Yelp and Chowhound to today’s FoodTok stars, audiences remain interested in food,” she concludes. “That’s a promising thing for the future of food criticism.”