X: How did this book come about?

KB: Will Guidara and I had flirted with writing a book together. Our book was going to be about pre-shifts, and we both had the same literary agent. We couldn’t sell it. I developed a relationship with David Black, a great literary agent. He said, “I think you’re a good writer. Do you have any other ideas?” I pitched him four ideas. He hated them. I said, “I’ve got something that’s kind of personal, but, man, I don’t know if I could put this out there yet.” I told him the story, and he said, “That’s your book.”

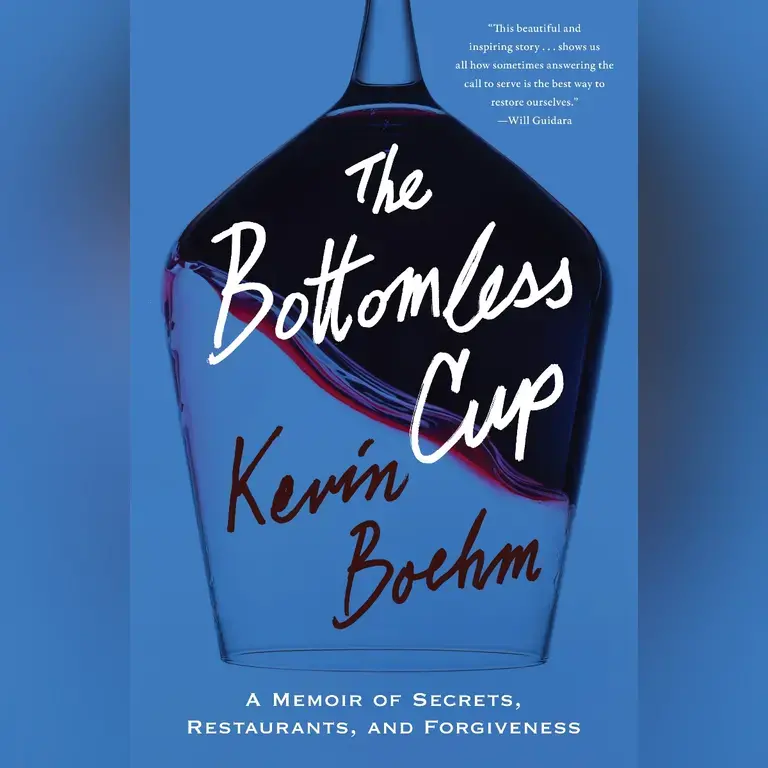

I wrote 70,000–80,000 words, and he shredded all of it and told me to start over. I understood, and I rebuilt it in a different way. We put it out and sent it to 24 publishers. We got a few offers, and it landed at Abrams.

X: Why tell this story now?

KB: I was at a crossroads in my life. A lot of stuff was happening, from my mom dying to my marriage falling apart to the idea that my restaurant group might not survive the pandemic. I was confused, upset, and angry, and this process of writing the book, no matter if it landed somewhere or sold, was something I needed to do for myself. I was writing to try to figure out who I was. At the very beginning, I thought it was never going to be out there for the world to see.

X: Tell me more about your experience surviving the pandemic.

KB: A group of us got together as the Independent Restaurant Coalition (IRC). The first meeting had 17 or 18 people on the phone, and they were all alphas. It was like an All-Star game. By day three, it was tense—everybody was struggling.

A week later, after we all dropped our guard, for the first time ever, I sat with people and we were vulnerable. You’re so afraid to be vulnerable in this business. You’re so afraid to say, “God, it’s really slow at my restaurant,” because you think as soon as that creeps out there, it’s just going to lead to you going out of business.

For the first time in my life, I heard people say, “Man, I’m scared. I’m scared my restaurant’s gonna go out of business.” And we did post-shift every day, which meant somebody getting up to speak. We had Donnie Madea saying, “I’ve got to close Blackbird next week.”

That group remains in touch to this day. We’ve all been more open with each other about what’s going on. We bonded together through the IRC when we had one goal: we all needed to survive. There was a kind of disbanding afterwards. We’re still not there yet in working as a collective to make legislative change, but it’s better.

X: There are similarities between 2020 and what’s happening now. This time around, there’s a heavier attack on immigrants who make up a big portion of the service industry. What does the situation look like now?

KB: Immigrants—maybe more than anybody—have been my mentors. They’ve been my teammates. There’s no chance I’d be where I am right now without their hard work and support within my restaurants. And the fact that we still haven’t figured out a solution for an industry that constantly has want ads out, when there’s a whole group of people who want to come to America to work in these restaurants, is a problem. These jobs aren’t being taken away from anybody.

X: There’s a lot of sacrifice from service workers that goes into great hospitality, including masking and minimizing their needs. You talk about this being a requirement to create exceptional customer service in the book. Given your mental health struggles, do you still feel this is the best way?

KB: Nobody likes a sad bartender. I think that’s what I wrote in the book. I still believe that.

The idea of pre-shift, beyond the education of a new dish or wine, is to get people to a high emotional level where they can give the best hospitality possible. There’s also a pre-shift that should happen after the pre-shift, which is individual. So if a manager notices somebody is struggling, they can check in with them and ask, “What can I do to help you?” That’s really the goal of a great manager: knowing the people who work for them. There’s got to be a little bit of the show in fine dining. You don’t want to be thrown a couple of menus at a restaurant and have someone say, “Sorry, I’m in a shit mood tonight. What do you want to drink?” We all have to play that game a little bit.

X: Do you have something formal like this in place at Boka?

KB: It’s something I talk to managers about.

X: How was the experience of writing this and revisiting some pretty heavy and dark things?

KB: Well, I didn’t write every chapter in order. I had to be in a certain space and energy to be able to write about suicidal ideation and to write it in the right way. It wasn’t fun, but it was cathartic.

X: Are there more moments like this that didn’t make the book?

KB: Yeah, of course. There are some things you keep to yourself. I got some very good advice from someone who read an early draft who said, “You will hope a few years from now you were as kind as possible to everybody in the book.” When I looked at both my fathers, I wanted to still be empathetic and careful about everything I said about them. The picture I painted of people in the book is fairly accurate.

X: In the book, you reveal yourself to be a big music and movie buff. If you lost everything and had to rebuild, what songs or movies would you have on repeat to keep you motivated?

KB: I love “Both Sides Now” by Joni Mitchell. It’s probably my favorite song of all time. Basically, every part of it is about the tension between illusion and reality, and in the end, she chooses the illusion. It makes me cry if I think about it too much.

I created, I created an illusion, and I still believe in it.

The second isn’t a song or a movie but a poem: “If” by Rudyard Kipling. When I thought everything was going to go out of business, I would read this poem to myself all the time. I can’t read it without getting very emotional. This was very important to me when I was building my life back up.