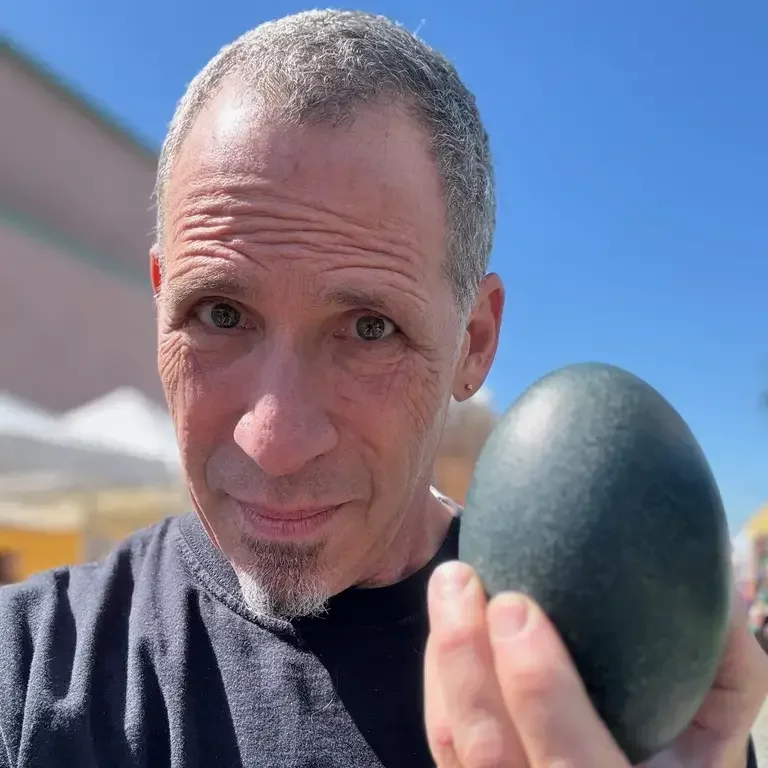

He was six when he cracked his first egg. Not because he wanted to cook, but because his mother told him to make his own dinner if he didn’t like what she was serving. So he did. Standing on tiptoe at the stove, little more than a boy with a spatula, Jeff Strauss felt it—power, joy, defiance, control. The egg wasn’t perfect. But it was his. And that was everything.

Decades later, after a long career writing punchlines for shows like Dream On and Friends, Strauss found himself drifting from the Hollywood machine. His kids were grown. His wife was still working. And he was growing restless—pitching scripts he didn’t believe in, chasing projects that no longer excited him. One day, his wife sat him down and said, “If you’re going to do something in food, you should do it while you can still stand up.” Strauss didn’t miss a beat: “It was unclear to me whether I could stand up.”

Before he ever opened a restaurant, Strauss lived two lives. By day, he was a television writer and producer, working on a string of sitcoms over three decades. By night—often in the middle of writing blocks or emotional spirals—he cooked. Not casually. Not occasionally. Obsessively.

“Cooking is the thing that I'll do when I'm stressed. It's the thing that I'll do when I'm happy. I will do it collectively. I will do it alone,” he said.

Cooking became the creative fugue state that writing never quite could be. He could spend a whole day at the stove, worn out but elated. But after a day of writing, even a successful one, he never came home to write more. He came home to cook. That imbalance, he admitted, only became clear in hindsight.

“I didn’t want to run a restaurant,” he said. “I always thought I was too smart for that.” But the joke, he admits, was on him. As Hollywood began to ignore him a little more each year, the idea he’d spent decades resisting finally took hold. He started staging at Ink and Miminashi in his mid-50s, forcing his body—aching joints, fading eyesight and all—into the brutal rhythms of kitchen work. He came home each night feeling like he’d been hit by a bus. Then he went back the next day.

Because unlike the writer’s room, this was his. No networks. No development hell. Just sharp knives, hot pans, and food that made people feel something.