Insights & News

Stay ahead of the curve with the latest: Discover breaking culinary news, fresh restaurant launches, exclusive chef interviews, and thought-provoking articles.

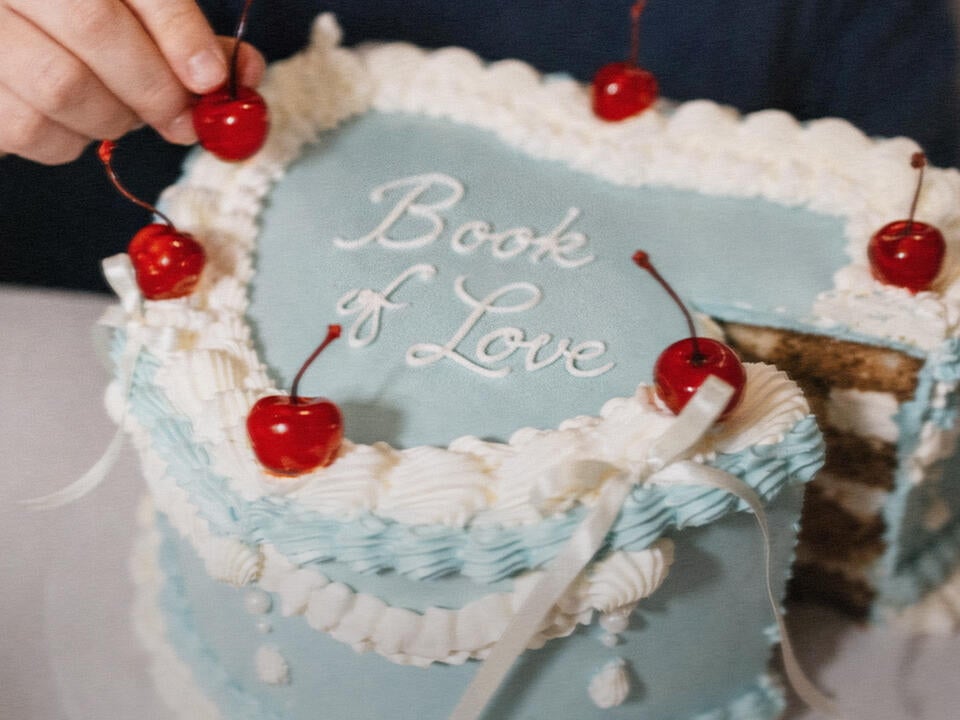

Take the survey and unlock a special romantic menu designed for two

Trending articles

Lists

Recipes & Drinks

Top restaurants

Hacks & Shortcuts

Series