These days, everyone’s a critic. From opinionated bloggers and social media commentators of varying quality and reliability (and inevitably without the beneficial filter of an editor) to highly-paid experts from prestigious magazines, diners confront an avalanche of opinion when choosing restaurants, and those restaurants must satisfy not just a handful of notable celebrity critics, but a smart phone-wielding, Instagramming, Yelping covert army. This is good for democracy: the decisions over whether a restaurant is good or bad, great or terrible, is no longer with the elite few, and the restaurants cannot rest on their laurels after the New York Times has printed their opinion, but have to be consistently good, because any one of their guests could, and probably will, publish their view.

On the other hand, there is so much text, so many opinions to wade through, that it can get downright confusing. We tend to think it is normal for a quick google of a restaurant to reveal hundreds, if not thousands, of reviews of varying length, quality and professionalism. For example, one of the best New York's restaurant, Le Cirque in New York, has 723 reviews on one crowd-sourced website, Yelp, alone.

It was not always this way. The origins of restaurant reviews date back a very long time, and it is only in the last few years, when everyone carries a miniature phone-shaped computer in their pocket and crowd-sourcing is considered as legitimate a rating method as expert investigation, that a revolution has taken place.

The origins of restaurant reviews

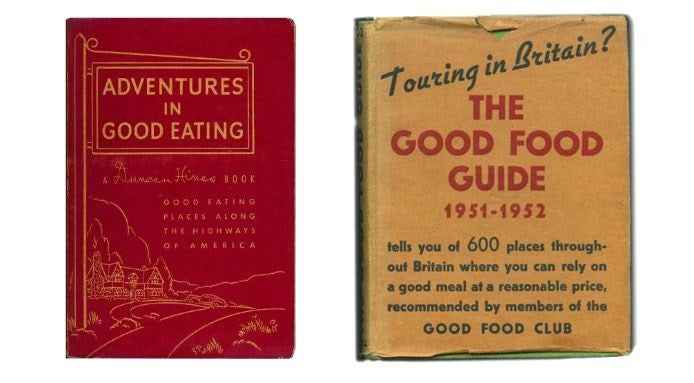

The role of professional restaurant reviewer comes a good deal later, with the rise of newspapers. The wonderfully (and complexly) named Alexandre Balthazar Laurente Grimod de La Reyniere published an annual Gourmands’ Almanac in France in the first decade of the 19th century, which is considered the first restaurant guidebook. Hugely popular, it encouraged fellow gourmands to seek out the best eats around, taking advantage of new travel methods (rail and later automobile) to seek culinary adventures. But this is as much a guidebook, foodie travel writing, as it is restaurant reviewing in the modern sense.